Language and National Security: Q&A with Bill Rivers

In today’s increasingly global world, collaboration can come from anywhere — and so can national security threats. The United States’ national defense agencies have to be prepared to deal with foreign intelligence, security threats, and diplomatic relations in a variety of languages, which increases demand for language skills across the board. Bill Rivers, a Planet Word Advisory Board member and the executive director of the Joint National Committee for Languages, weighs in on how national defense agencies handle these language challenges, how they’ve changed, and where they’re headed next.

Q: What role does language play in national security?

A: Language has been a critical element of national security since World War II. For most of the past half century, language requirements reflected the bilateral world — since the primary adversary of the US was the USSR, Russian was the most important language to learn (and, to a lesser extent, the languages of the Eastern Bloc). Of course, languages such as Korean and Vietnamese saw greater requirements during those conflicts, and our diplomatic engagements demanded a wide range of languages, as they covered essentially every country.

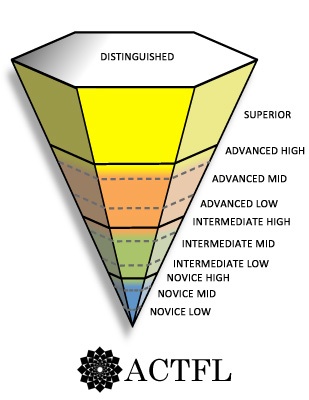

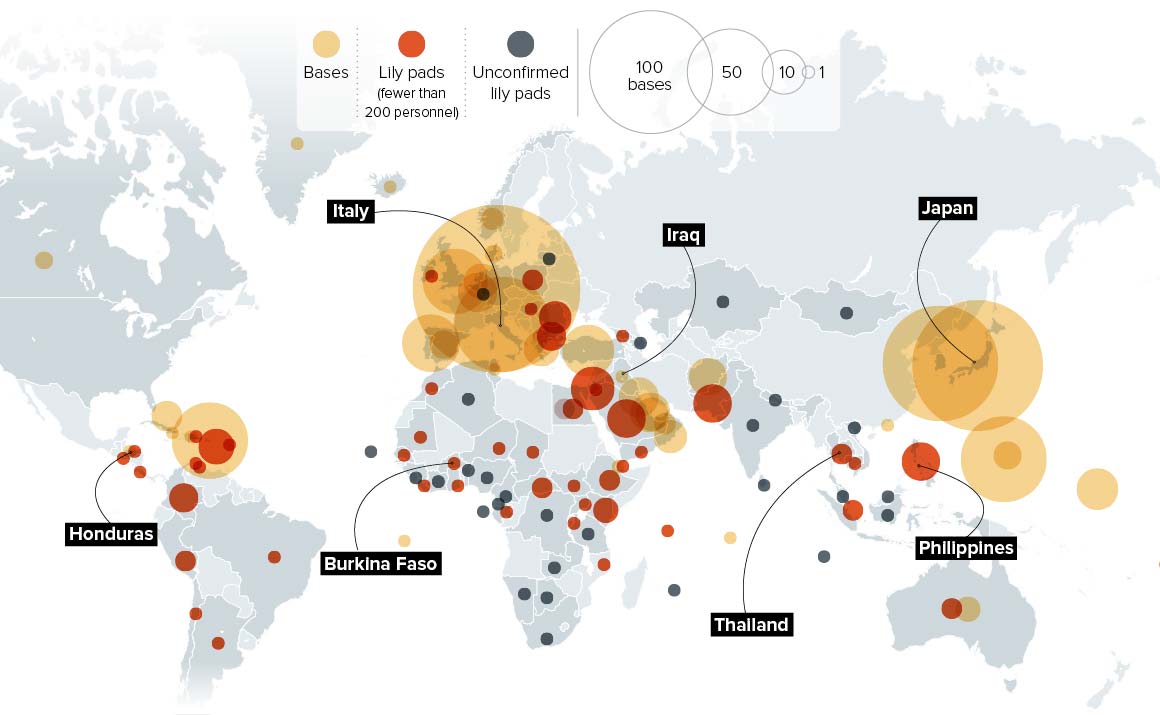

The last two decades have drastically altered that environment, as our national defense strategy was forced to account for uncertainty and unpredictability in international relations beyond the traditional focus on specific threats from specific countries. This has led to significantly heightened requirements for language in national security. The worldwide scope of defense, intelligence, homeland security, and diplomatic responsibilities means that more languages are needed, and more folks speaking and using them — and for more missions, such as cybersecurity, special forces, and counterinsurgency. Finally, the level of proficiency required for most of these missions is now at the “3” or “Superior” level — which is a full level higher than a generation ago.

Q: What languages are particularly in demand?

A: One can read the newspaper and see that we have engagements all over the world: the Middle East, Southwest Asia, China, the Korean Peninsula, Russia. There’s a growth of Islamic fundamentalism in parts of sub-Saharan Africa that’s driving a demand in the federal government for those languages. Trade with Africa is driving a demand for African languages. In the mid-term, unless the geopolitical situation changes or calms down considerably, we’ll probably continue to see demand for Arabic, Chinese, Russian, Farsi, and Korean. Again, read the nearest papers or look at a map and you’ll see where the key languages are.

The Critical Language Scholarship program of the State Department currently lists Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Indonesian, Azeri, Russian, Turkish, Arabic, Bangla, Hindi, Persian, Punjabi, Urdu, and Swahili as key languages. The National Security Education Program lists 50 languages. Each agency determines which languages are critical.

Q: What languages do you think will gain significance in the future?

A: Long-term it’s harder to say. A lot of us thought after the Cold War ended that we’d see a reduction in overall military intelligence requirements, and it turned out that that was completely off.

Things happen suddenly. When the Balkans fell apart, we were unprepared linguistically. We scrambled to retrain Russian-speaking personnel in Serbo-Croatian. Somali was a real challenge — at the time, there was a very small Somali-American community. Pashto was a challenge because, again, there’s not a big community in the US. Often for the really small languages there’s only a handful of scholars.

It’s very hard to predict where trouble will occur. I’m sure at some point we’re going to need some language we’re not necessarily well-prepared for.

Q: How has the translation process changed since you were a translator and interpreter?

A: I started in 1989 when I was an undergraduate. The hardest thing was I had no formal training or preparation and didn’t realize that there was such a thing. And I think a lot of Americans who are learning languages or who are bilingual, however they acquired their language knowledge, may not realize there are methods for translation and interpreting that make your life a lot easier. There are special note-taking techniques, for example, for consecutive interpreting (where the interpreter waits for the speaker to finish his or her entire statement before translating) as opposed to simultaneous interpreting (where the interpreter and the speaker talk at the same time). I had no idea about the use of terminology databases, translation memories — databases of phrases, sentences, and language fragments that have been previously translated — and things that were in their very earliest stages and really weren’t broadly available when I was starting. My terminology “database” was a three-ring binder that I kept terms and definitions in. I had a couple bookshelves full of dictionaries I’d acquired over a ten- or fifteen-year period that are mostly obsolete now.

Translation is completely different nowadays — it’s all done on a computer screen using web- and cloud-based tools for the most part, even in fairly low-density pairs (language pairs that are less frequently translated). If you’re working on a large translation project, you may be one of a very large team of people all over the world, working on one discrete part of the project, and have other people trying to put it together. That’s really different from translating treaty documents and agreements 25 years ago, where you would write it out longhand and someone else would type it up.

Q: Could computers ever replace human translators?

A: Language technology goes back almost sixty years. As a linguist, and an occasional computational linguist, I’m skeptical that an app, or language technology, will ever approximate the “Universal Translator” from Star Trek, or the Babel Fish in Douglas Adams’s Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. What technology has done is take care of the more rudimentary tasks in translation, in particular — the “who, what, where, when” questions. Deeper questions like “Why?” and “To what end?” are very hard for computers to answer. We still need humans who know other languages and cultures to be involved in language work. Moreover, when we talk about face-to-face interactions in real time, there’s no substitute for an interpreter, or a language-enabled diplomat or investigator.

Bill Rivers is the executive director of the Joint National Committee for Languages, a coalition of language organizations that works to ensure that all Americans have the opportunity to learn a second language.

Bill Rivers is the executive director of the Joint National Committee for Languages, a coalition of language organizations that works to ensure that all Americans have the opportunity to learn a second language.