From the Andes to the Big Apple, Keeping an Indigenous Language Alive: Q&A with the Quechua Collective

With up to about 10 million speakers, Quechua (also known as Runasimi, or “people’s language”) is the most widely spoken Indigenous language of the Americas, and it is an official language in Peru, Ecuador, and Bolivia — it was even the primary language of the Inca Empire! However, despite its historical prominence, Quechua faces mounting challenges from dominant languages like Spanish and English, pushing it to the linguistic margins and leading to a decline in intergenerational transmission. The Quechua Collective of New York endeavors to combat this trend by preserving and revitalizing the Quechua language and Andean culture with a community of native speakers, heritage speakers, and students in the New York area. We spoke with Douglas Cooke, the Collective’s Director of Education, about the organization, the Quechua language, and challenges that speakers face to keep their language alive.

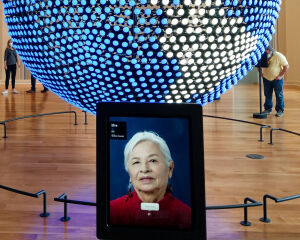

In the Spoken World gallery, you can learn about Quechua from Quechua Collective founder Elva Ambía Rebatta.

Q: Why is it important to teach Quechua language and Andean art and culture in New York?

A: Elva Ambía founded the Quechua Collective in 2012 because she believed it was important to keep Quechua alive. She loved the language and missed being able to speak it with her friends when she moved from the sierra to Lima as a child. When she came to New York in the 1960s, she had to learn English as well, and between working and raising a family she had little time to think about Quechua. But she kept the culture alive by singing and playing traditional Andean music, and eventually started the Collective to teach the Quechua language and celebrate Quechua culture in New York.

Why is all this important? Although Quechua is the most widely spoken Indigenous language of the Americas, with several million speakers, many parents to do not pass it on to their children, partly for the same reasons Elva experienced — lack of time, moving to the big city where it is not spoken as much, the need to learn Spanish or English to find work — but also because for centuries Quechua people were ashamed of their own language. They were invaded by the Spanish, and Spanish became the language of the victor. Racism and discrimination compelled many to conform and hide their heritage. Even today, many people speak Quechua at home but do not speak it outside. The legacy of racism imposes shame on the speakers. The mission of the Quechua Collective is to teach, preserve, and diffuse Quechua so that the language thrives and the stigma vanishes.

Q: What is your favorite part about working at the Quechua Collective? Do you have any stories?

A: We are a dedicated bunch, and it is an honor to team up with hard-working people who all share the mission of valorizing Quechua. But my favorite part is writing the textbooks. (I’m working on my third book, Quechua Cusqueño Year Three.) I write the textbooks specifically to overcome drawbacks I’ve found in other textbooks, which don’t provide enough exercises or don’t explain how a word or construction is used, or just don’t go far enough. There are very few textbooks that go beyond the first-year level.

I also asked our other teachers the same question. Here’s what they have to say about the Quechua Collective:

Emma (our teacher in Paris):

My favorite part is, first: seeing the students understand new concepts, apply them, and get more and more fluent in the process; and second, devising and refining a teaching method to reach that goal. For students to build fluency, I try to break down the grammar and the exercises as much as possible, down to the smallest suffix, so students don’t feel overwhelmed but rather assimilate new constructions little by little through speaking. My biggest challenge is having them understand without relying on translation and the written word, but rather by listening and understanding within the cultural context. Not all Quechua speakers read and write in the language, so being able to understand through listening and speaking is key.

Rodrigo (our teacher in Lima):

My favorite part of working for the Quechua Collective is sharing the knowledge I learned from my family and community. It is gratifying to be a bridge between the children of immigrants and their Quechua culture. The students tell me they really enjoy learning about our music and customs.

Q: How do the younger generations interact with Quechua? Are they doing interesting things with the language?

A: It’s an exciting time to be involved with Quechua. There are many musicians out there singing rap and pop in Quechua (Liberato Kani, Renata Flores, Lenin), and many more who are sparking interest in Quechua through the traditional songs (Alborada, Inkarayku, Renzo Aroni). There is a literary magazine in Quechua, Atuqpa chupan (“the fox’s tail”), and there are conferences devoted to the language. Professor Americo Mendoza Mori founded the Quechua Alliance at the University of Pennsylvania, and their conferences get bigger every year. There are student groups in several universities. There are video series and podcasts. More and more movies are being made partly or entirely in Quechua, and many of them get international distribution and win prizes.

All of this makes Quechua exciting and appealing. Many of our students are young people in their 20s who want to explore this side of their heritage. They know their Hispanic culture, but they also know that there is another side that has perhaps kept quiet, and all these new developments in Quechua culture make it easier, and fun, to explore that side.

Q: How do you combat the trend of declining speakership?

A: As I said earlier, many parents are not teaching their children Quechua, either because of the stigma, or because they feel learning Spanish or English will give them more opportunities. We can’t deny that, but it would be a pretty boring world if everyone knew only the colonizer languages and forgot the Indigenous languages that offer unique ways of expression. The boom in Quechua culture helps to combat this, but my own small part, I feel, is to show how interesting the language is. I’m not Andean, but I am a language nerd, so my role is to show how fascinating and funky the language is, how it can do things English and Spanish cannot. We hope that as more and more second language speakers of Quechua emerge, native speakers gain pride from already knowing a language that others value so much and spend so much effort to learn.

Q: Are there any resources you would like to share with people who are interested in learning more about Quechua or Andean culture?

A: I honestly believe the Quechua Collective of New York is one of the best places to learn outside of academia. We have great teachers who are passionate about what they do, who care very much about their students’ progress, and who don’t count the hours when it comes to helping them: answering questions, giving feedback, doing extra review sessions, or creating new teaching material to suit their interests. Emma is developing new teaching methods that free students from a reliance on reading and writing, and emphasize speaking, oral storytelling, and music, in collaboration with our house band Inkarayku.

As for other resources, YouTube is a great place to start. For beginning students, there are scores of people teaching introductory Quechua. More advanced students can follow @WilfituYachachiq (from Bolivia) and @solischa1202 (from Cusco). For people who want to read Quechua, an excellent resource is Peru’s Ministerio de Educación, which publishes dozens of children’s books in Quechua, some of them with Spanish translations. They are all available to download for free on their website.

Q: To close in the spirit of our Spoken World gallery celebrating the world’s languages: What is your favorite word or phrase in, or linguistic tidbit about, Quechua?

A: There are so many interesting things about Quechua, it’s hard to pick just one! I’m particularly fascinated by Quechua’s variety of suffixes. Quechua has fewer words than English, but you can modify those words endlessly with a smorgasbord of suffixes. There are suffixes to convey that you are doing something for someone else, for pay, or just for fun. Some suffixes tell you that something is happening suddenly, slowly, habitually, for a long time or repeatedly, whether something is happening somewhere else, or in many different places. There are evidential suffixes that signal whether you are speaking from experience, or repeating what you’ve heard, or guessing. The verb rimay means to speak, but rimapakamuwashasqa means “They say he was muttering at me from a distance.”

If I had to pick a favorite work in Quechua, it might be añañáw, which expresses appreciation for something delicious or beautiful. It’s not an adjective but an interjection:

Paltata apamuykiku. (We brought you avocados.)

Añañaw! (Yummy!)

Emma:

If I had to pick a favorite word, I’d choose mama which can mean — depending on the context and how it’s used — “mother” or “lady.” Quechua shares this word with many other languages (in the sense of “mother” in particular), but I like how endearing mama sounds in Quechua; you can call any woman mamáy which means “ma’am/señora,” but it carries more affection than it does in Spanish and English. It’s quite impossible to translate. Growing up, my grandmother would call me mamasita, meaning “little mother” (or so I thought), and I never understood why she called me like that since I was about six years old! It’s probably my favourite word, because I now understand where it comes from, how much affection it carries, and I love hearing it being used to/from/among women when walking in the market in Peru, for example. (The same can be said about the term tayta, meaning “Sir/dad,” but my grandmother never called me papacito for obvious reasons!)

Rodrigo:

My favorite word in Quechua is Tupananchikkama because it expresses the Quechua feeling of wanting to return to a person you have just seen. For me that is a great example of the feeling that the Quechua community experiences and expresses.

Douglas Cooke is the Director of Education at the Quechua Collective. He is the author of Quechua Cusqueño, Year One and Quechua Cusqueño, Year Two. The Quechua Collective of New York is comprised of native Quechua speakers, heritage speakers, and students from the New York area. Their mission is to preserve and diffuse Quechua through classes, workshops, and cultural events, to support Quechua speakers living in NYC, and to allow the language to be shared with the greater community and generations to come.