New Words in the Digital Age: Q&A with Grant Barrett

Photobomb, binge-watch, humblebrag, face-palm, side-eye: these are just a handful of words added to Merriam-Webster’s dictionary in 2017, but they’re markers of a much larger lexical explosion. The incredible amount of text circulating across the internet means that new words are reaching wider audiences at faster rates — and dying out just as quickly. But what does this rapid turnover mean for dictionaries, which attempt to capture the ways people use language? Grant Barrett, lexicographer and co-host of the radio show A Way with Words, weighs in on the lifespan of new words and the complicated role of the dictionary in this ever-changing landscape.

Q: Has the internet changed the way new words and phrases enter our language?

A: Probably the most important lexis-related thing that the internet has done has been to drastically increase the overall volume of text the average person in the United States produces and reads each year. Compared to 30 years ago, it’s like people are reading and writing an extra encyclopedia worth of text each year. All those small snippets of social text add up and they matter lexically!

What that means is that people more often come across new written language and they have more opportunities to recycle it. Some of us recycle it a lot, some of us not at all.

And, because of the always-on nature of modern communication and the 24-hour news cycle (not just internet: text messages, television, and radio still count), when new language is shared, it goes out to more people at one time more quickly.

Which means that trendy and faddish words not only catch on faster, but they peak faster and they burn out faster.

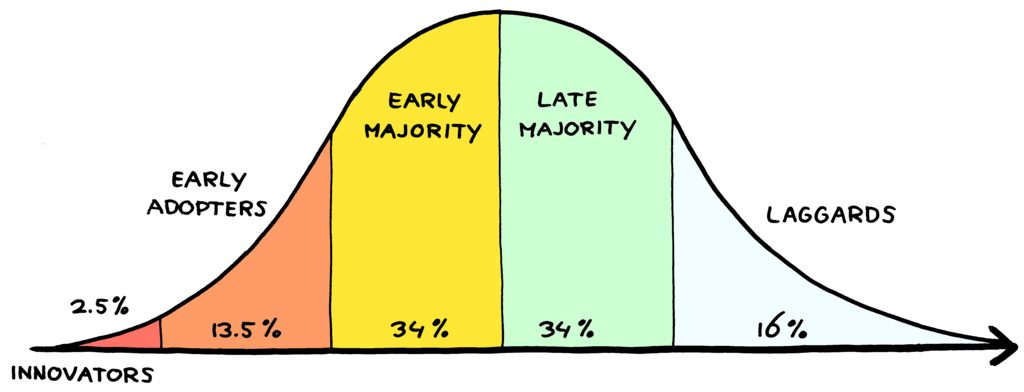

This is a well-known curve:

Roger’s Innovation and Adoption curve roughly charts the way an innovation (in this case, a new word) comes to be accepted by different groups of people: first the innovators, then the early adopters, and so on.

All of those roles are still happening: early adopters, late adopters, etc. You still have people out of the loop. But that leftmost date and that rightmost date are now much closer together than they were 30 years ago. (I’d add a label after the peak: “early adopters scorn late adopters and move on to the next thing.”)

For the specialists — the lexicographers, in particular — the internet has made it super easy to find, track, and research new language. There are ways to automate finding new words, for example. If we can count the digital periodical databases as “internet,” as that’s how we access them, then it’s no contest. I can dig into stuff like never before.

Q: Where do dictionaries enter that process? What makes dictionaries important and relevant in today’s world?

A: I say this as a former dictionary editor and a cofounder of an online dictionary, so I don’t say it lightly: I don’t see a happy place for most dictionaries in the modern world. Although one, as a lexicographer, may get a great deal of satisfaction out of gathering up all the latest words, and defining them well, and finding out their histories, the truth is that most of your work will go unnoticed. While we may gather up all the new words, and we may put up press releases or get some momentary notice in the press and on social media, the overall impact of a dictionary’s ability to bring new words and new language to the people is minimal.

Also, as I wrote on the “about” page of my Double-Tongued Dictionary:

“There is a great fascination with ‘brand new’ words, but it is time-consuming and logistically difficult to find new words immediately after their birth. They are hidden at first, and usually propagate slowly. There are many. Most die young. Even if they could all be trapped, skinned, and mounted, the end result would be uninteresting, since most new words are scientific and technical and about as fun as sandpaper.

We could fill this entire web site with new words that will never be heard from again. However, it’s more interesting for me and you if I log words which show at least some sort of acceptance before their status as ‘new’ words is recognized.”

I think that’s the space that dictionaries kind of occupy now: most of what they capture is old new-words rather than new new-words.

Q: What are the biggest misunderstandings people have about how dictionaries are made?

A:

-

“What do you mean you’re a dictionary editor? I thought the dictionary was finished!”

-

When you show them a new word they didn’t know: “That seems fake to me. Are you sure it’s real?”

-

When you show them a new word they already knew: “That’s not new! Why would you include that?” All words are new to somebody at some point. It’s like that William Gibson quote: “The future is already here — it’s just not very evenly distributed.”

-

They say “The Dictionary” like there’s a single all-encompassing monolithic work. There are many dictionaries and they can be very different from each other.

-

They think the Oxford English Dictionary contains all words. It doesn’t.

-

They think Urban Dictionary is a reliable source. It isn’t!

-

They think lexicographers make up the new words rather than find them.

-

They think if a word isn’t in “The Dictionary” then it’s not a real word. That’s false! No dictionary comes anywhere near to including all the words.

Q: Since new words and phrases are being coined all the time — in relation to pop culture, current events, and every aspect of our lives — how do you figure out which words will fade out and which will continue to be used? Essentially, what gives a word staying power?

A: Allan Metcalf expertly tackles this question in Predicting New Words: The Secrets of Their Success.

He calls it the FUDGE factor:

- Frequency of use. More use over more time.

- Unobtrusiveness. This surprises people! Generally, words that are too cute, too funny, or too creative have less success.

- Diversity of users and situations. More people, in more places, in more contexts. This is why organized campaigns to promote a particular word usually fail.

- Generation of other forms and meanings. They are used to make other words or other parts of speech or other longer expressions.

- Endurance of the concept. What it refers to needs to be long-lasting.

Q: Are there any words you’re watching right now?

A: Am I! I have thousands of words to look into in my “word tips” file, and these are (some of) the ones that I thought most worth sharing with listeners and guests at my events, as well as the ones that weren’t taboo (because I have a whole bunch of those, too).

Grant Barrett is a co-host of the nationwide public radio show A Way with Words, author of Perfect English Grammar, and a lexicographer who has worked on the Oxford Dictionary of American Political Slang and founded the online Double-Tongued Dictionary.

Grant Barrett is a co-host of the nationwide public radio show A Way with Words, author of Perfect English Grammar, and a lexicographer who has worked on the Oxford Dictionary of American Political Slang and founded the online Double-Tongued Dictionary.