Balinese, Meet Wikipedia: Revitalizing a Local Language Online

With pressure from English and Indonesian driving local languages like Balinese to the linguistic margins, a passionate group of speakers is working to make sure the language and its culture don’t disappear. Their plan? Give Balinese a second life on the internet. Led by founder Alissa Stern, the BASAbali initiative is developing an online home for the language with interactive wiki technology. She spoke to Planet Word about the challenges of digitizing the traditional language and the importance of being proactive in revitalization efforts.

Q: Why revitalize Balinese — and why right now?

A: Traditionally, what has been done with language revitalization is to wait until a language is endangered. We feel like at that point, it’s too late. Our feeling is, if you have any opportunity to turn a language around, you have to intervene much earlier.

Balinese has about a million speakers; on the other hand, only about a quarter of the population of Bali can still speak it. So it’s in a state of decline, but it still has a solid base, which is why we’re intervening now.

We are trying to encourage the local population, who is influenced by globalization and nationalization, as many local languages are, to value their own language. But we are also trying to say to the world that local languages are important, that monocultures of any sort are not sustainable, whether they’re languages or agriculture or animal species. The planet thrives on diversity. Even though a person may not have a particular connection to a local language, there is value in having a diversity of local languages in the world.

Q: How did you choose to structure your revitalization efforts? Why a wiki?

A: It actually started with a dictionary written by Fred Eiseman, who was an American who lived in Bali for years and wrote about everything Balinese under the sun. He died about five years ago, and his widow, via Eiseman’s assistant, Linud, bequeathed us the dictionary — on condition that we make it public. So that was the original piece of the wiki. We started it in 2014, and through the years we’ve expanded from Eiseman’s dictionary to including thousands more words and sample sentences — contributed by the community — and an encyclopedia section as well.

We also wanted to engage both the local and the international communities, both scholars and community members, to work together to create this resource. We felt that there was a real value in getting these groups to be actively engaged, not for us to create it in a vacuum.

When we looked around, Wikipedia was just getting going, and we thought, that’s it! We’ll use wiki technology, which is engaging, and which is shown to be pretty reliable and accurate — which astounded people at the time. We thought that this could be a new way of engaging people and creating resources at the same time. This could create that really important link between scholars and community members, which is hard to bridge.

Q: Could you walk us through the wiki a little bit?

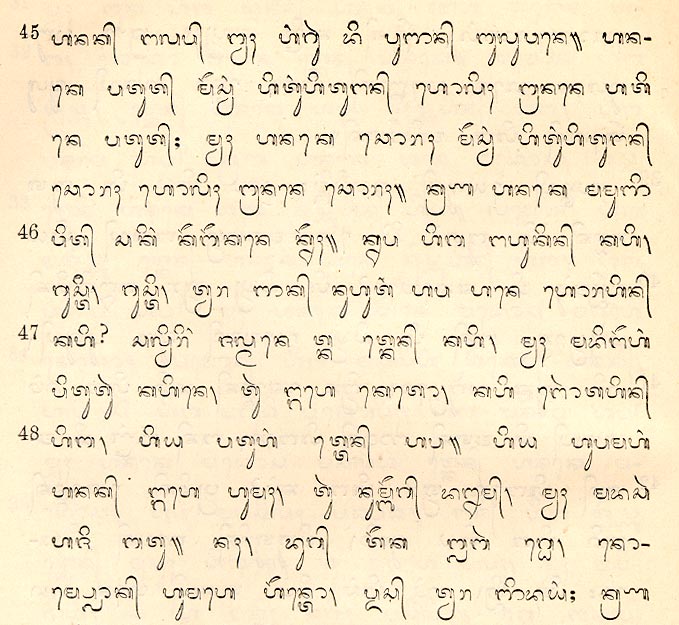

Balinese script on parchment

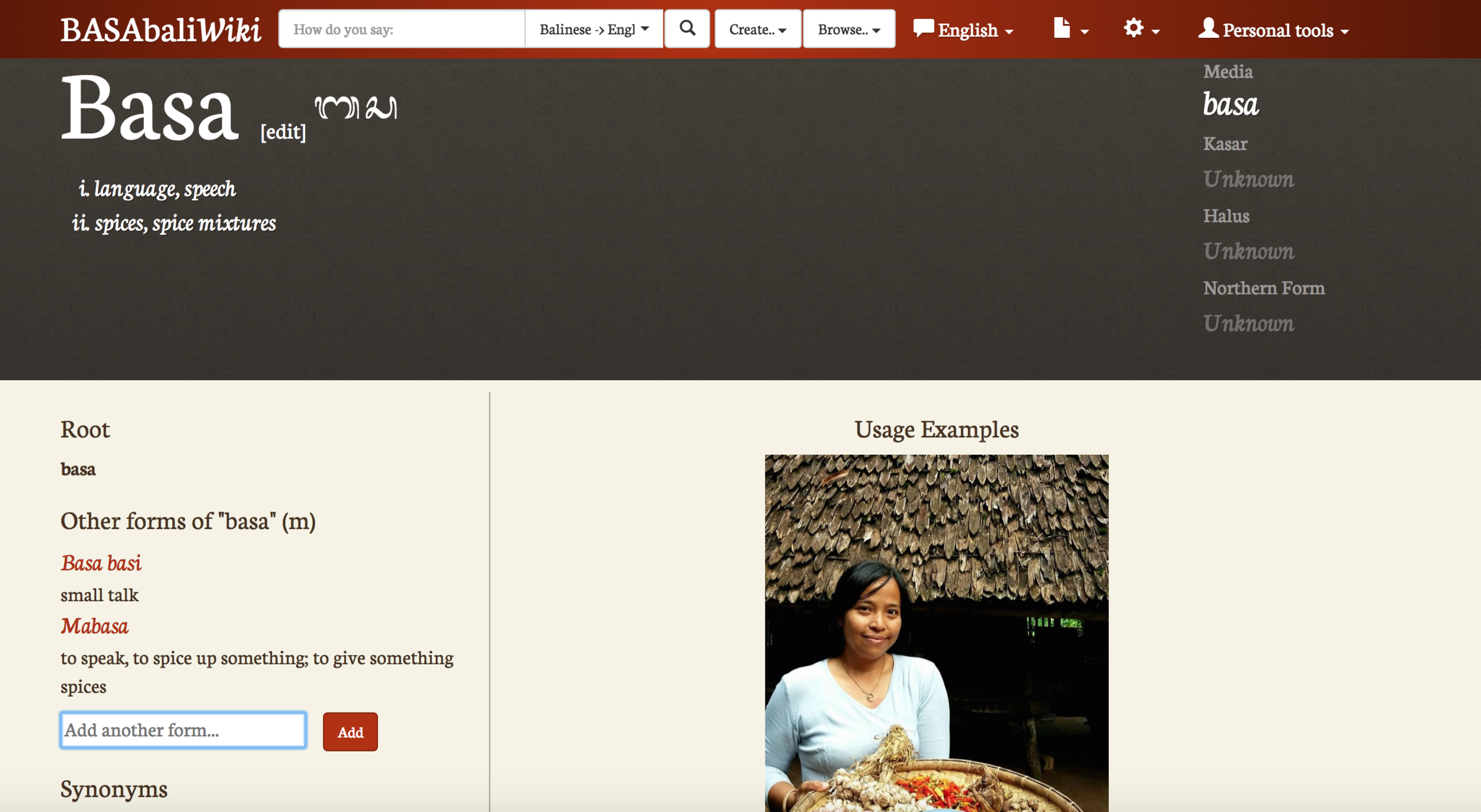

A: Let’s start with an easy word: basa is a Balinese word; it means “language” or “spice.” I love that combination, that double meaning. This is a typical entry: you have the word in Balinese [using the Roman alphabet] and, if possible, the word in Balinese script.

We have the definitions, and those are entered by a 15-person team of linguists, and another team of about seven or eight Master’s or Ph.D. students in linguistics. Then we ask the community to give us sample sentences, using the word in context with the kind of language that they use now, and we have a team of editors translating the sentences into English and Indonesian. People send us photos and videos too, so that users can see and hear people using Balinese in context. Our next plan is to tag the videos and photos to Google Maps so that we can capture regional variations.

As I mentioned, basa means “spice” as well as “language,” so someone sent us a photo of Balinese spices. Someone else sent us a video saying a sentence using the word “basa.” Not all of our users have internet service, so sometimes people just hand us a flash drive with videos to upload to the wiki.

This is the entry for the word “basa” on the BASAbali wiki. Notice the definitions and the word in Balinese script on the top left, the different levels and forms of the word on the top right (which, for this word, have not yet been submitted to the wiki), and the user-submitted photograph at the bottom.

Q: Did you run into any problems with the writing system when creating the wiki?

A: Balinese is traditionally an oral language. The sacred texts of Bali are written in Kawi using Aksara Bali (Balinese script). Balinese script is taught in schools for about an hour or two a week, and there’s a push to teach every schoolchild the ability to write and read in this script. But for the most part, Balinese is now written in Latin letters. It’s a very complicated writing system and there has been difficulty in getting the Unicode for the script to work completely accurately, so social media has reduced the use of the script even more. To encourage as much participation as possible, we decided that the wiki would primarily use Latin letters as the regular interface, but to also provide a way for entry words to be written in Balinese script.

Q: What other challenges have you faced in trying to put Balinese online?

A: Our primary challenge is internet service! Large sections of Bali do not have internet access in their homes (including the homes of our linguists!). People access the internet through mobile hot spots through which they can easily text and access Facebook, but they do not have sufficient bandwidth to upload videos or to access the wiki website. A volunteer just made an app that streamlines access and editing, but internet access, especially for uploading videos, is still a problem. We’re now working on developing an app game to engage young adults more actively in the site.

Balinese presents yet another level of difficulty in that Balinese is stratified. In order to speak it properly, you have to choose different forms of words depending on who you’re talking to and what you’re talking about. If you’re on Facebook, or other social media platforms, you don’t know who’s reading it, so you can’t place yourself in relation to the reader. Users/speakers find it very difficult to use Balinese.

Balinese traditionally has five or six levels or more, depending on how nuanced you want to be. It’s not only as in French where there’s the word tu and vous depending on the formal or personal relationship between speaker and listener — in Balinese, this stratification exists in every word, and not just in pronouns. On the wiki, we include the top three most common levels that the language is flattening to. You will have “media,” which is the middle level — it’s everyday Balinese — and also the lower level and the higher level.

But you don’t always stay in one level when you’re speaking. For example, let’s say you and I are peers, so I would use a peer-to-peer language when I am talking with you. But if I want to elevate your coffee because I think it tastes particularly good, I would use the word for “coffee” from a higher level. And that is a subtle way of saying the coffee is really good or sacred or important, even though you and I are on the same level. The whole thing is a very complicated system, and if you put it on social media it’s even more complicated because you don’t know who you’re talking to when you post on social media.

On top of that is an increasingly uncomfortable feeling among young Balinese that they don’t necessarily want to use a language that is so stratified. They’re looking for a more democratic system. That, in addition to wanting to be a part of the international community, is pulling them towards the national language of Indonesian, or the international language of English.

Now I think the scholars and the local community have come to accept a more flattened form of Balinese. That’s the way people are using it, the way people are posting on Facebook. It doesn’t follow all the rules. The levels aren’t precise. It’s mixed with English and Indonesian. But that’s the way people are using it, so we’re embracing that. Languages evolve. Let’s embrace where Balinese is now, and let’s also embrace where Balinese traditionally was, and the wiki allows us to do that.

At the time of this interview, over a third of a million people were using BASAbali’s wiki to learn about Balinese and contribute their own knowledge. The site is constantly being updated and revised, but the project doesn’t end there. To aid in their revitalization efforts, the BASAbali team has developed language-learning software. They also host monthly crossword and meme contests, post phrases and biographies of Balinese artists and writers, and hold workshops to get more people involved in the wiki.

Alissa Stern is the Founding Director of BASAbali.