The Wit of Washington: Remembering Legendary Political Humorist Art Buchwald

“You can’t make up anything anymore. The world itself is satire. All you’re doing is recording it.”

— Art Buchwald

Before Stephen Colbert, Jon Stewart, and Trevor Noah, there was Art Buchwald. Planet Word recently announced the installation of a typewriter belonging to Buchwald, whose syndicated Washington Post column reached millions worldwide. The typewriter is on display in the Schwarzman Family Library but could just as easily belong in the nearby Joking Around gallery, given Buchwald’s innate sense of humor. In this interview, Art’s son Joel Buchwald talks with Planet Word about his father’s life, legacy, and love of making people laugh.

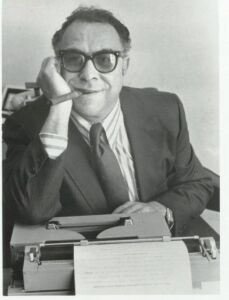

Buchwald with one of his many typewriters. Photo courtesy of the Buchwald family.

Q: The museum is now the proud home of one of Art’s typewriters. Do you have memories of him at a typewriter?

A: Dad was a gadget guy. He loved gadgets. Never knew how to use any of them, but he would always buy whatever the latest thing was. He was a correspondent in Paris when tape recorders first came out, and he’d gotten one. He and [journalist] Ben Bradlee were going down to some big event, so Dad said, “Don’t worry, we don’t have to take notes, we’ll record it.” Of course, it didn’t work, and no one had any notes.

But typewriters were another gadget, and he always had the latest typewriter. He loved them. He had a second office at home, and he’d work in the evenings if he wasn’t going out to dinner or an event. He was always either on the phone, on the typewriter, or going through newspapers and magazines looking for story ideas. So, the typewriter was an intricate part of his life. That’s how he communicated his ideas and his thoughts. And when he typed, he pecked. He didn’t type with all ten fingers, just two.

Q: How did he start writing political satire? That’s not how he began his career.

A: That’s right. He started his journalism career in Paris, and his column was more social. When President Dwight Eisenhower went to Paris in the late ‘50s, Dad wrote a spoof column poking fun at Eisenhower’s press secretary, James C. Hagerty. Hagerty called it “unadulterated rot,” but the Paris press loved it. Dad’s name was in the headlines. After that, I think he realized he could take this back to the States and write political satire. And he did just that. He created his position. He created his job. Before him, no one else really did what he did. There were newspaper columnists, but they were serious guys. There was nobody who did humor like he did. In Washington, he really created a new persona for himself.

Q: How did he balance humor and commentary in his writing? Was one more important to him?

A: Humor was always the most important thing to him. It was something he learned at a really early age, as a kid. It provided him with a mechanism to deal with other people. He grew up in foster homes. He never saw his mother, she was hospitalized right after he was born. He had three older sisters, and his dad made curtains, but he didn’t have enough money to keep the family together. So they were farmed out to foster homes, and he also spent a lot of time at the Jewish orphanage in New York. So, he realized that by using humor, he could get what he wanted; he wouldn’t be bullied, and people would leave him alone. So right from an early age that became a key component to the way he dealt with life.

In his work, the commentary was secondary, frankly, because he used humor to make his point. Without the humor, I don’t think anyone would have paid any attention to him. But the commentary was very important, because he was able to articulate it through humor. He was really proud of columns where he took a stand that may or may not have been popular. He was against the war, the Vietnam War. And he was for civil liberties. He was for freedom.

Q: What role do you think your dad saw himself playing in politics and in the media?

A: To some extent, he thought of himself as the joker, the court jester. Because he would point out the foibles of a political leader, and he would make fun of them. But it was never malicious. He was not a mean person, and his columns weren’t mean. He would point out that something was crazy, but he did it in a fun way. And so, you would laugh.

There’s this story about Lyndon Johnson, way back when he was president. He was waiting for a Cabinet meeting to start, and his press secretary was sitting there, reading the newspaper, and just laughing. President Johnson said to him, “So what are you laughing at?” And he said, “I’m reading Buchwald’s column.” And it was about Lyndon Johnson. And Johnson said, “You think that’s funny?” “Oh, no, Sir. No, Sir. No, Sir.”

But that’s who he was. He was funny, but he wasn’t trying to hurt people. He just wanted to make people laugh. He didn’t think of himself as some guiding light, telling people what to do. He simply saw his role as pointing out the things that weren’t right or weren’t working. And he didn’t see himself as someone who was going to change the world. He just hoped to bring a smile to everybody’s face in the mornings.

Q: Can you think of a particular column that may have shifted or influenced a political debate?

A: I think he did that with almost every topic he wrote about. Because he was able to open people’s eyes to a point of view they weren’t naturally thinking of, whether it was about gun legislation or civil rights, abortion or gay marriage. He used to say, for instance, that gay people should have the same opportunity to go through what everybody else goes through when they go through a divorce. So he would take issues and try and present it in a way that would make people go, “Oh, well, you know, he’s got a point.” With humor, he could broaden people’s perspectives.

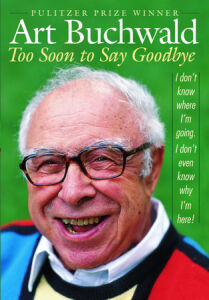

Buchwald’s final book, Too Soon to Say Goodbye.

Q: Art wrote a bestselling book in hospice — he kept writing until his final days. Why do you think he did that?

A: Writing, and his column, was his lifeblood. That was what kept him alive. His column had become who he was, and it was really, really important to him. Late in life, things slowly started being taken away from him. The speeches and social engagements became fewer and fewer. Everything that he had built up was slowly being taken away, but he held onto his column. And when he was in hospice, he dictated that final book, because writing is what he did. He was in a position where he could keep doing that. Most people have to retire. You can’t keep working. That’s it. But Dad was lucky enough to have an outlet, and an audience, until his final days.

Q: Art’s typewriter is located in the Schwarzman Family Library, where you can hear testimony from people about books that are important to them. Are there any books or authors that were especially important or influential to Art that you could share with us?

A: One of his favorite writers was Ernest Hemingway. For a number of reasons, I think. Hemingway was sort of a man’s man, and he lived in Europe and Paris, like Dad. But Hemingway also wrote in short, declarative sentences. He didn’t write really long, flowery sentences. And that’s the way Dad wrote, too. It was short, straight to the point. He loved Bill Styron and Truman Capote and Norman Mailer, too, but he really had a soft spot for Hemingway.