The State of Literacy in the Digital Age

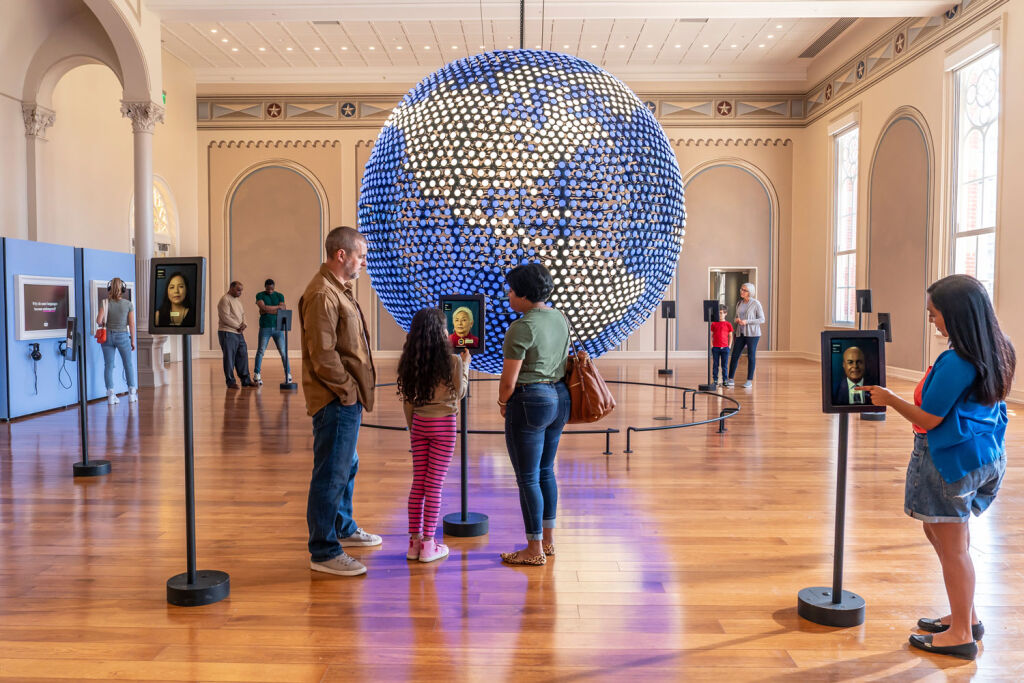

Five years ago, Planet Word opened its doors with a bold mission: to spark a love of words, language, and reading in people of all ages — at a time when global literacy rates were already in decline.

Today, that mission is more vital than ever. Recent findings from the OECD’s Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) reveal continued challenges in literacy worldwide. What’s driving this downward trend — and how can we help students build stronger reading skills?

Planet Word Advisory Board member Andreas Schleicher, OECD Director for Education and Skills, shares his insights below.

Over the last decade, most countries in the industrialized world have seen steady declines in the reading performance of 15-year-olds, as evidenced by the tests of OECD’s Program for International Student Assessment (PISA). Many have associated these learning losses with school closures during the pandemic, but in most countries this downward trend started way earlier, somewhere between 2012 and 2015. More recently, OECD’s Survey of Adult Skills has exposed a similar downward trend in adult literacy (though not numeracy).

There has been much speculation about the reasons for this downward trend, but one obvious factor is changes in our reading behaviors. A decade ago, many of us read more complex texts than we do today. We read books that required us to build mental representations of complex contexts, imagine and navigate the perspectives of different figures and characters, and synthesize nuanced arguments. Today we consume the bite-size marmalade of digestible answers spat out by ChatGPT and its many friends.

We often assume that digital devices prepare students best for the digital world. But results from PISA suggests that the best predictor for literacy skills is the time students spend reading long pieces of text in paper format. Reading digital texts more frequently showed a negative association with reading skills. In contrast, reading fiction texts and reading long texts more frequently was positively associated with reading skills. On average across OECD countries, students who had to read longer pieces of text for school (101 pages or more) achieved 31 PISA score points more in reading than those who reported reading smaller pieces of text (10 pages or less), after accounting for students’ and schools’ socio-economic profiles and students’ gender. That’s the equivalent of an entire school year.

The most worrying finding from PISA is that the reading skills that are atrophying fastest are the higher-order literacy skills that are most crucial for success in our AI world, such as navigating ambiguity and distinguishing fact from fiction.

These days it is tempting to see AI as a force that steadily erodes human agency. But this shouldn’t be a slow retreat; us yielding more and more ground to algorithms. Education should help us become more than the sum of isolated, automatable tasks. The rise of artificial intelligence should sharpen education’s focus on human capabilities that cannot be reduced to code — our capacity to navigate complexity, to exercise judgment in uncertainty, to create something genuinely new. Reading literacy is at the heart of these. Reading literacy is not just a beautiful word or predictor of better economic outcomes, it belongs to the central pillars on which we build our societies and democracies. And if we don’t protect such human capabilities with determination, artificial intelligence could wash away the very foundations of our societies.