The Book Doctor Is In: Q&A with Bookbinder Emma Kiely-Hampson

All book lovers know that any day is the perfect day to sit down with a new book or an old favorite, but sometimes the realities of life leave our favorite books a little worse for wear. When you’re feeling out of sorts, you go to the doctor. But where do you bring worn-out books? To a book doctor, of course!

This National Book Lovers Day, we’re celebrating some of the unsung heroes of the book world who make the books we love and breathe new life into family heirlooms: bookbinders. We asked local bookbinder and restorer Emma Kiely-Hampson to talk about her experience and shed light on her field.

Q: How did you become interested in bookbinding? And how do you become a bookbinder?

A: My interest in bookbinding was initially an interest in fixing my own books. I had been a collector of old books for a while but realized there were some I loved that needed a little bit of help. I was an apprentice for a few years and then became the lead bookbinder at a local bindery, but the work I do usually requires a degree nowadays. I don’t have the degree required to work within a museum setting, but as a commercial binder I am well equipped and trained to take care of books of many varieties.

Q: What kind of books do you typically work on?

A: In the last few years, the majority of books I have worked on boil down to religious texts, cookbooks, theses, and notebooks. The range is pretty wide, but the books that are used the most are the ones that come my way. I made a few books as well, including notebooks and a baby book.

Q: What exactly is bookbinding? How do you bind a book, and how has it changed over time? What materials do you use?

A: Bookbinding is a few different things, but essentially it is the making and maintaining of books. The binding process is a bit different for each book, but at a basic level you have one piece of material, two pieces of board for a cover and a piece for a spine that are all glued together and the material is wrapped around these pieces. The book itself has its pages sewn together until it becomes what is known as the book “block” and is then attached to the cover, usually with endsheets, to secure it all together. The trade of bookbinding is pretty old, dating to just before the medieval period realistically, so it has changed dramatically over time. I’m not sure I could correctly describe it without giving an entire history lesson and then some, but the introduction of machinery has made the most dramatic impact on binding, and still does. As for materials used, for any book it can range from leather to fabric, card stock to cardboard, embroidery thread to waxed thread.

Q: Do you find ways of expressing yourself in your work?

A: Because the materials are varied but the book may require a particular material, there are times where the creativity aspect of my work can get diminished. My main objective for all of my work, however, is to give the client something more than they asked for. This might be the addition of some new endsheets or the careful folding of leather edges around a board. This might also be in the choosing of the material to replace what can’t be salvaged to maintain the style and look of the piece without sacrificing its integrity. With the new binds there is of course a lot more freedom, but even those pieces can have requirements. I think, to shorten my answer, my creativity in each of my books is in the details.

Q: As a museum all about language, we love learning new words. Does bookbinding have any special terms or jargon?

A: My favorite jargon in bookbinding actually has more than one name: crash, mesh, or spine lining. This is the material that is glued against the spine of the book block to create more integrity and flexibility at the most utilized section of a book. Without crash (my favorite one of these names), the book can more easily fall apart because there is less for the pages to hold on to in order to stick together. One of my old teachers, actually, helped to develop a thesaurus for bookbinding jargon. The thesaurus can be super useful for those just learning because bookbinding is such an old art, and it spans countries and generations, so things are named and renamed and renamed again. A multiple-name substrate like crash is not uncommon. And two of the names for this substrate that I know aren’t even in the thesaurus yet! That’s how varied it can get.

Q: What is your most memorable bookbinding or book restoration experience? Any funny stories?

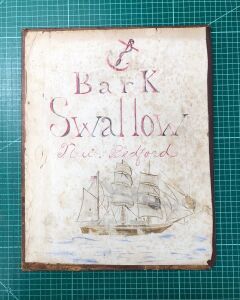

An illustration in the 1880s whaling log book that Emma restored.

A: There was one book that came into the bindery that really needed some love. It was a cookbook without any covers that had been well used, and obviously someone loved making the cookies in the book because these pages were stuck together. So I made it some new covers and sewed it together and cleaned the pages and the client came back to pick it up and almost shouted, “Oh my god, it’s a book!” It made me laugh, and it was so nice to see someone so happy, both with my work and their family heirloom restored to its former glory.

There was another book I loved restoring that was a whaling log from the late 1880s that was unfortunately covered in cat pee (hard fix) but also needed some rebinding. What I loved about it, though, was all of the drawings on it. Some sailor had drawn their ship on the inside cover of the log and colored it in, and then on the leather on the outside had done line drawings of faces. It was such a departure from the intended content of the log and it was so human that it almost made me cry.

Q: Do you have any advice for someone who wants to work with books or become a bookbinder?

A: Keep going. It’s a small, weird, wonderful business that requires some real grit and dealing with people who don’t necessarily understand what you do, but it is so worth it. Creating and restoring books is such an incredible experience, and if you want to be a part of it, there are plenty of resources and avenues of research that can help you get there.