Remote Control

A while ago I was invited to be a judge for the 2022 Aspen Words Literary Prize. My husband, Tom Friedman of the New York Times, had served a 9-year stint on the Pulitzer Prize jury, which he always called “the best book club in the world,” so I was eager to have a similar experience. I imagined that jury deliberations would be like book club discussions taken to a new level, and serving as a judge would offer me an excuse to say, “Sorry, I can’t do that [whatever unpleasant task needed doing] right now — I’ve got to finish this reading!”

Because, ironically, while working to start Planet Word, a museum designed specifically to celebrate books and reading, I probably had read the fewest books in my entire adult life. I skipped meetings of my 32-year-old-and-counting book club because I hadn’t read the selected books (no time, eyes too tired); I ignored the growing stack of books on my nightstand (too tired, early morning meetings); and I spent my few free hours doing crossword puzzles and the Spelling Bee to boost my word-world bona fides (and fight dementia). Of course, truth be told, I was still reading reams, but mostly emails and contracts and articles about museum operations or linguistics — subjects with immediate utilitarian value but hardly counting as literature.

So being on the Aspen Prize jury offered me a chance to get back in the habit of sustained, deep reading of literature. I really looked forward to rebuilding my reading self. I looked forward to uncovering cutting-edge literary trends and boundary-pushing authors. Now I’d finally be able to recommend books to friends with the authority that comes from having actually read the books!

The $35,000 Aspen Words prize is awarded to the author of an “influential work of fiction that illuminates a vital contemporary issue and demonstrates the transformative power of literature on thought and culture.” What a wonderful way to describe the power of a great book!

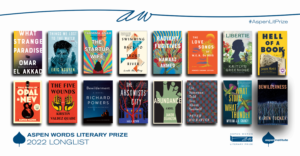

As a judge I was asked to read and evaluate 16 long-listed books based on two criteria: the quality of their writing and the illumination of an important contemporary issue. I am still in the middle of reading and rereading them now.

As I read them for literary merit, I consider the freshness of the imagery and sentences, the originality of the plot, the author’s ability to sustain a tone from beginning to end. This first half of my judging assignment is often awe-inspiring — I marvel at how the authors find new ways to turn a phrase, to structure a novel, to introduce readers to characters never-before encountered, to twist a familiar plot. Truly amazing.

But if reading through that lens is often delightful, I have found it almost unbearable to read book after book addressing the kinds of daunting societal problems these novels tackle: socioeconomic inequality, environmental degradation, immigration, racial inequality, violence and war, gender inequality, mental illness, and political identity, as enumerated in the Prize’s mission statement. Starting out, I wondered if I could stand reading 16 in a row.

But to my surprise, something important and positive has grown out of that difficult assignment. I’ve found that my unrelenting dive into our world’s thorniest problems has grown my empathy, rather than deadened it. I’ve discovered that if characters win my sympathy or elicit understanding for their actions, I find myself drawn into their world and hoping for solutions. I don’t want to give up on these people or ignore their dilemmas. Such is the power of good writing and superb storytelling.

And that’s what I’ve always argued is the reason for a museum promoting reading: that only by building a nation of readers can we hope to cultivate the empathy we need to understand people facing unfamiliar and difficult situations, people not like us. By putting ourselves in others’ shoes, by being enveloped in a good book, we exercise the understanding and critical-thinking muscles that we need to make good choices in everything we do — from the votes we cast, to the policies we support, to the stances we take. We are forced to ask ourselves, honestly, whether we would have made the same or different choices as the character who stumbles or succeeds.

So that’s what I’ve been doing for the past few weeks — engaging with these meaty issues and meeting unforgettable characters and asking myself what I believe.

But even buried in all this reading, I also had time to listen to the deliberations and voting for the American Dialect Society’s Word of the Year on Jan. 7. Insurrection was the winner, which I thought was the proper choice for 2021, a year so defined by the divisions in our country exposed on January 6, but Tom said he would have chosen a different word: remote.

It wasn’t one of the nominees, but when I thought about it, I thought Tom made a good argument. Two thousand twenty-one was the year screens of all types divided us, physically and socially. Children and teachers resorted to remote classes; meetings and social gatherings were held remotely (even my book club); patients met with doctors via telemedicine. But now I have an antidote: Reading.

Funny to recommend being alone with a book to combat solitude and increase understanding, but that’s what my intense period of reading has done. Reading has shown me how to become closer to people, to understand their choices and relationships, to explore their worlds. I think we’ve just forgotten how that happens. I know I did. So here’s my resolution for the new year: Turn off the screens and pick up a good book.

I should never let books become a remote part of my life again.

— Ann Friedman, founder, Planet Word