Prison Reading

So the latest financial outlaw and crypto-currency-exchange fraudster, Sam Bankman-Fried, was quoted in an interview prior to his downfall and arrest as proclaiming “I would never read a book.” Who knows whether he was trying to shock or exaggerate or cover up for reading difficulties, but his flippancy certainly caught my attention.

Self-proclaimed nonreaders like him give credence to Planet Word’s belief that a literate population is the foundation of a strong democracy. (And by that I mean one governed by the rule of law.) Wide reading informs our moral imagination, it instills the tolerance we need to get along with our fellow-citizens, and it builds empathy when you put yourself in other’s shoes and explore their worlds.

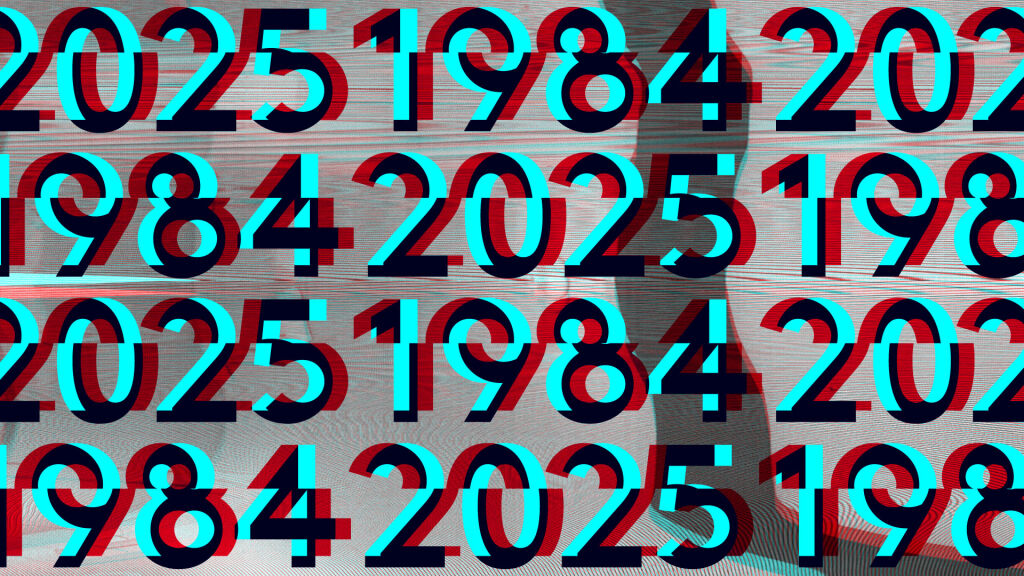

Disturbing, then, that the number of people who are able to read but choose not to applies to a growing number of Americans. The Pew Research Center reports that only 23% of adults say they have read a single book in the past year. The percentage of elementary and middle school students who said that they had “read for fun on [their] own time almost every day” in the 2019–20 school year were at their lowest points since the question was first asked in 1984. Add to that the estimated 20% of students who will struggle to learn to read easily and fluently, and the estimated 5% who may be truly dyslexic and face that additional neuro-processing challenge.

In the case of beginning readers, we adults have only ourselves to blame if students find themselves frustrated and unable to read by the end of third grade, which demarcates the end of learning to read and the beginning of reading to learn – for instance reading about social science, science, or math. No beginning reader should be blamed for not reading if they haven’t been adequately taught or taught without appropriate, relevant materials or have been asked to read books that have no relevance to their lives or concerns. (If parents want more say in their children’s education, then insisting on high-quality reading curricula is where to start. For a controversial, but mostly persuasive, primer on this subject, listen to the podcast “Sold a Story.”)

Shame on us for letting our schools adopt beginning reading curricula that don’t track with the proven, evidence-based, phonics-based, science of reading. Schools of education also bear some of the blame for failing to train future teachers with the most cutting-edge, validated reading curriculum. And I don’t just mean elementary school teachers — all teachers, no matter the grade or subject they teach, need to be trained as reading teachers to some extent, because they will be sure to teach some English-language learners or will have students who aren’t proficient readers despite their grade or age. They will have students who need to be able to decode and define longer, multi-syllabic words that come their way in upper grades; they will be responsible for teaching challenging, unfamiliar concepts and vocabulary.

As quoted in a New York Times story called “In Memphis, the Phonics Movement Comes to High School” on December 26, the Rev. Althea Greene, chair of the Memphis-Shelby County public schools, said: “When you realize that students are missing skills, I don’t care where they are, from ninth to 12th grade, we have to stop and we have to address it.”

And we also know that a high proportion of low-level readers fill our prison system. That is why it was especially disturbing to read a January 2022 Washington Post piece that reported that book-banning is especially pervasive in prisons. The decades-old organization Books to Prisoners reported that the “need for educational and self-empowering materials in prisons is vast. Despite this need, prisons routinely impede access for arbitrary and biased reasons, a practice long overdue for public examination.” When reading is such a prerequisite to success, providing books that these potential readers can relate to is essential.

Some inmates have the good fortune to learn to read or improve their reading in prison classes or by being exposed to books in a prison library. Take the striking story of Reginald Dwayne Betts. He was arrested for participating in an armed carjacking when he was 16 and sentenced to prison for nine years, during which time he began to read and write poetry. He eventually earned a Yale Law School degree, was awarded a MacArthur fellowship, and founded a nonprofit called Freedom Reads, which provides access to books to the incarcerated through Freedom Libraries.

Therefore, it really alarms me that anyone — here’s looking at you Mr. Bankman-Fried, MIT graduate — would brag about not reading. In fact, not choosing to read when you have the ability and the access to books strikes me as almost criminally negligent in and of itself.

Brag about the latest book you read that you wish everyone would read and discuss. Brag about the number of pages or books you’ve read in a year. Brag about your new knowledge of philosophy or history or culture or even leadership and entrepreneurship. Brag about your favorite author. I wouldn’t mind that kind of bragging! But please don’t brag about not reading!

But come to think of it, maybe we don’t need to worry about our country’s most-recent, notorious non-reader. If convicted of his alleged crimes, he’ll have plenty of time to read behind bars, and let’s hope that the books by the authors he learns to enjoy — espousing ideas that build the common good — will be awaiting him there.

— Ann Friedman, founder of Planet Word