A Couple of Neologisms for Today

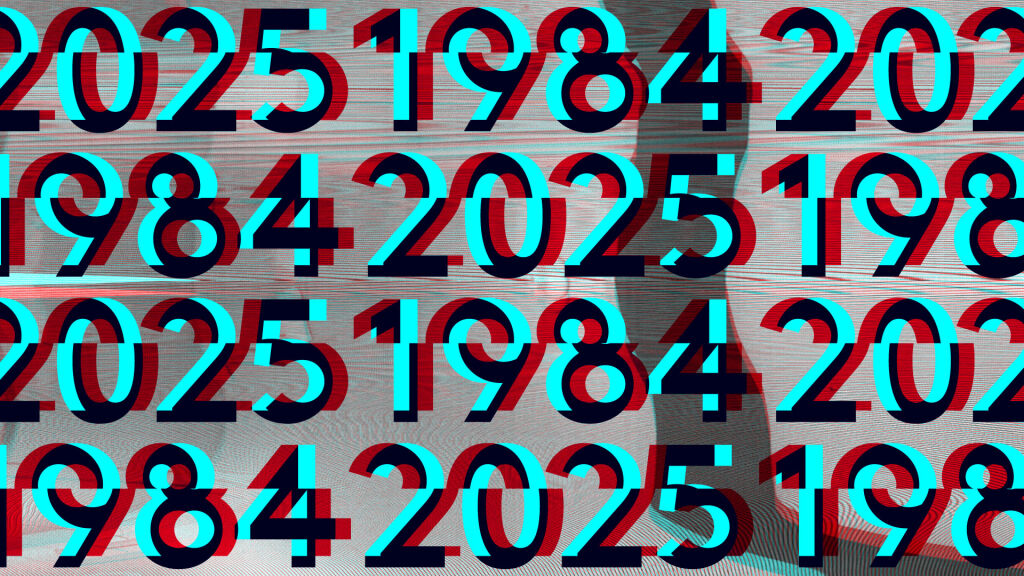

On November 29, 2022, Planet Word interviewed Dr. Hany Farid from Berkeley about his work to identify deepfake online videos and photography. This is especially important as we enter the 2024 election season — we hope that our votes are based on truth.

Dr. Farid’s presentation for Planet Word was detailed and fascinating, and by the end, I would say, he left us with a modicum of hope that such fakery would ultimately be exposed through careful examination of images and voices. He noted that there are certain tells that a video or image is fake: someone wears unmatched earrings or their head movements are atypical of their speaking style.

But today I read that fake videos are getting easier for amateurs to create and share — they’re so easily produced now, there’s even a new name for them: “cheapfakes,” a word coined by Britt Paris, an assistant professor of library and information science at Rutgers. In a story in the New York Times (March 12, 2023), Paris says you don’t need sophisticated computational knowledge anymore to produce these deepfakes; a free app can enable you to literally put words into someone’s mouth.

And is too often the case with new technologies, bad actors are usually the early adopters. The Times article said that 4chan, a message board “known for racist and conspiratorial content,” has already used these cheapfake tools to issue hateful messages. Therefore, to accompany the new noun cheapfakes, I propose a new verb: crehate. Too often that’s what these tools are being used for — to create hate, slander, libel, and confusion.

ElevenLabs is one of the technology companies whose software enables users to synthesize and replicate voices in seconds, to spread made-up stories to thousands on Twitter or TikTok. Alarmed at what their technology was enabling — often fake videos of celebrities and politicians saying things in what seem to be their voices but which they never uttered — the company suggested collaborating with other A.I. developers to create a “universal detection system.”

As if these cheapfakes weren’t enough of a challenge to people seeking the facts, we’ve also witnessed stunning revelations in the Fox News/Dominion Voting Systems lawsuit in the past couple weeks.

Even though the Fox hosts clearly admitted they had no evidence that Dominion’s voting machines were faulty, Dominion may still lose its defamation suit against Fox and its friends, because Dominion has to prove, according to the New York Times (March 12, 2023), that “Fox News either knowingly broadcast false information or was so reckless that it overlooked obvious evidence pointing to the falsity of the conspiracy theories about Dominion” — a high bar for the prosecution.

The article quotes defamation experts as saying that Dominion’s strongest case will be if it is able to “point to specific examples when individual Fox employees responsible for a program had admitted the fraud claims were bogus or overlooked evidence that those claims – and the people making them – were unreliable.”

But according to the Washington Post (March 7, 2023), Fox is defending its coverage by arguing that it’s “plain as day that any reasonable viewer would understand that Fox News was covering and commenting on allegations about Dominion, not reporting that the allegations were true.”

Citing the landmark New York Times Co. v. Sullivan decision, “which held that public officials must show that false statements made about them had been made with “actual malice,” or with “knowledge or reckless disregard” in order to win defamation lawsuits, Fox lawyers argue that the accusations “were not so wildly improbable.”

Taking the two stories together, I worry about our future ability to ferret out disinformation and help consumers of news, and voters, discern the truth and make judgments based on facts. Supporting the truth and generating the trust that democracy is built upon gets harder and harder.

As mounting decades separate us from the Cold War experience with state-sponsored propaganda in the Soviet Union and Maoist China, few of us have first-hand knowledge of what living in a propaganda state was like and how it prevented people from knowing the truth and trusting news sources — how it inverted reality and trapped people in a bewildering world. But with President Putin’s insistence that Russia is carrying out a “special operation” in Ukraine and his criminalization of any descriptions to the contrary, we’re getting a taste of the surreal world that propaganda creates.

Democracy relies on the twin pillars of truth and trust. The outcome of the Dominon lawsuit and our ability to rein in cheapfakes — to create and not crehate — will have significant repercussions on our ability to trust and perpetuate our democracy.

— Ann Friedman, founder of Planet Word