What Tackling Complexity Requires

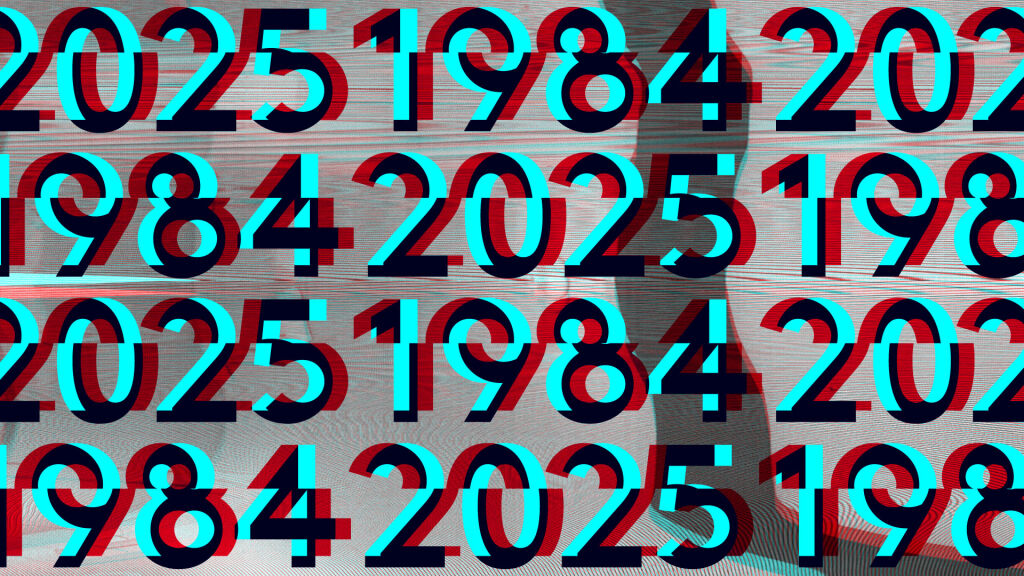

When I think about the issues raised (or ignored) during the just-past election season, so many of them are unhelpfully complex — e.g., vaccines and how to fight the spread of pandemics and childhood diseases, the definition of tariffs and how their imposition affects a country’s economy, whether there’s an urgent need to erect guardrails on AI and social media, how far to let freedom of speech proceed unfettered, whether to increase gun control, or the history of the Middle East conflict or Russo-Ukrainian relations.

Understanding and debating such complicated, knotty issues requires us to learn as much about the topics as possible by gathering a wide range of opinions. This is hard work! It might require holding contradictory ideas within one’s head and maybe even disagreeing uncomfortably with friends and family or a willingness to discard previously held beliefs. Thanksgiving-table discussions could be a tad heated again this year!

In my opinion, for Americans to make progress toward solving these problems, people will need the curiosity and doggedness of an investigative reporter or maybe even of a lawyer for the prosecution. They will need to follow the facts wherever they lead in order to form a well-grounded opinion.

Where do people develop those critical-thinking muscles? Certainly, social media and biased news outlets haven’t been helpful information sources. They are too often the sources of proven misinformation and slanted opinions.

Critical-thinking abilities should be the product of a class-A education, starting as early as adolescence. Think about middle school, when students are taught the principles of the scientific method; or geometry class, when students learn logic by writing proofs based on Euclidian theorems. Or in reading class, where students are asked to analyze character traits and motivations based on what those characters say or do. Or history or civics classes where, students are taught to base conclusions on primary source material. But this requires teaching a relatively new skill: lateral reading.

As our partners at the News Literacy Project define it, lateral reading dictates “instead of going deep, go wide.”

In his article “This Is the Future and Reading Is Different Than You Remember,” former classroom teacher Terry Heick says lateral reading “is the act of verifying what you’re reading as you’re reading it.” (The lateral reading concept and the term itself were developed from research by the Stanford History Education Group.)

As the News Literacy Project notes, “Lateral reading helps you determine an author’s credibility, intent and biases by searching for articles on the same topic by other writers (to see how they are covering it) and for other articles by the author you’re checking on.”

If you agree that these critical-thinking skills are largely developed and nurtured in schools, then you’ll be concerned, as I am, about incoming-administration promises to abolish the Department of Education, which also create a general atmosphere of mistrust around our public school, teachers, administrators, and librarians. And we’re already facing a national shortage of teachers! Relatively low pay and status combined with book banning and limits on teachers’ autonomy and classroom discussions hardly make teaching careers an attractive choice. (Remember the days when a post-college job with Teach for America was the coolest thing grads could do?)

Someday, as Planet Word board member Craig Mundie predicts in his new book about AI, Genesis: Artificial Intelligence, Hope, and the Human Spirit, co-authored with Eric Schmidt and Henry Kissinger*, all students may have access to a personalized AI tutor in their pockets, but until then, we need to support the teachers we have and the institutions we have that keep education fair and free and meaningful to all Americans.

Tackling tough issues, with or without the help of AI, will be the educational challenge we face in the coming years. Let’s hire the best teachers, train them well, provide adequate resources, and use all the resources at our disposal to be prepared.

—Ann Friedman, founder of Planet Word

To ferret out the truth when reading, the News Literacy Project advises readers to ask questions such as:

- Who funds or sponsors the site where the original piece was published? What do other authoritative sources have to say about that site?

- When you do a search on the topic of the original piece, are the initial results from fact-checking organizations?

- Have questions been raised about other articles the author has written?

- Does what you’re finding elsewhere contradict the original piece?

- Are credible news outlets reporting on (or perhaps more important, not reporting on) what you’re reading.